Friends of the Orangutans • 02 Sept 2020 | Last review • 09 November 2021

There are concerns over the unexplained fate and welfare of six critically endangered orangutans at the controversial Sepilok Orangutan Rehabilitation Centre (SORC).

The Sabah state government owns the SORC, and the Sabah Wildlife Department (SWD), the state government’s wildlife authority, manages the centre. The SWD has not demonstrated transparency to the public about these six apes’ current situation since June 2020. Their wellbeing and whereabouts are currently unknown to us.

What can you do now to help?

CLICK HERE to tweet to the authorities

CLICK HERE to sign and share our petition to demand transparency

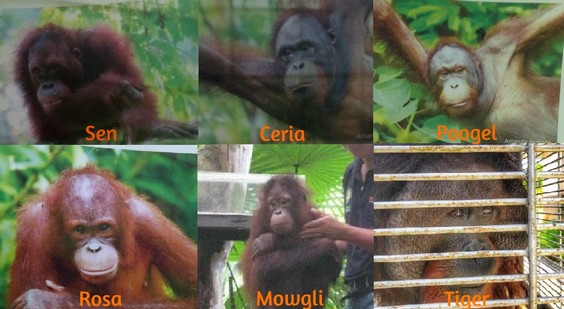

The six orangutans are Ceria (age 15), Rosa (female, 18), Mowgli (18), Poogle (17), Tiger (22) and Sen (15). They arrived at the SORC as infants – supposedly for rehabilitation to prepare them for wild release – after becoming orphans in the wild; their mothers might have been killed.

All six apes are humanised orangutans, and the details presented below also raise concerns if their rehabilitation may have failed, leading to welfare concerns for these apes.

Go to Orangutan humanisation (below) if you would first like to understand what the humanisation of orangutans is, its probable causes at the SORC and its impacts on the animals.

Why are the concerns for the six humanised apes?

Rosa, the only female orangutan among the six, was known to steal from items at the SORC and “her next victim”. Through no fault of his own, Ceria has displayed worrying behaviours, including attacking a SORC tourist. He has been injured by a pack of dogs near the centre – as was revealed in ‘Meet the Orangutans’, a maleducative 2016 Animal Planet documentary series about the SORC.

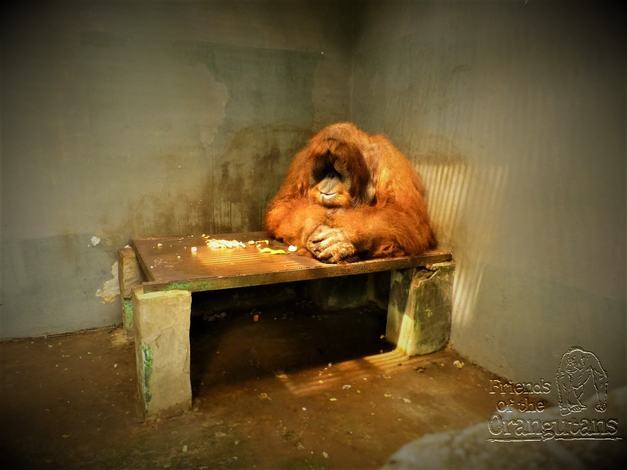

We were informed that Tiger has been kept in a cage at the SORC since December 2018 – after this ape’s second release into Tabin Wildlife Reserve* had failed.

We also discovered that before Tiger’s second release the founder of a British orangutan organisation that supports the SORC privately expressed concern that significant problems could arise if the media found out about Mowgli, Poogle, Sen, and Ceria’s behaviour. This suggests that these apes are a physical risk to tourists and staff (when left to roam around the centre). The SORC was apparently close to getting sued by a tour company for safety negligence (physical danger by a humanised orangutan).

Based on information from a source Mowgli, Sen, Ceria and Poogle are very terrestrial animals and have shown not much interest in forest life.

Allowing humanised orangutans to roam around the SORC may be a threat to staff and tourists. It could be a public relations disaster for the SWD and the ministry it is under, the Sabah Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Environment (KePKAS) if an orangutan injures another tourist at the SORC and the media uncovers it. It is no surprise then that besides Tiger, Ceria and Sen are apparently also kept in cages at the SORC.

No transparency from the Sabah Wildlife Department

An October 2019 Borneo Post news report indicated that Ceria and Rosa would be released from the SORC into Tabin. In January 2020, we wrote to the SWD to express our concern over the release plan and asked it to first present its release plans, and how the department made the decision to the IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group. We also asked the SWD to inform for how long post-release monitoring** (PRM) would be carried out.

After sending our third email, in June 2020, the Director of the SWD, Augustine Tuuga, responded that the department was exploring new forest release sites for SORC orangutans and that the SWD acknowledged the importance of carrying out post-release monitoring. Mr Tuuga also indicated that the SWD was contemplating building an enclosure to keep some unreleasable orangutans in, instead of confining them to life in cages. He, however, did not explain which orangutans have been deemed unreleasable, nor provide details about Ceria, Rosa, Mowgli, Poogle, Tiger and Sen.

Wild-releasing humanised orangutans that are known not to persistently show that they can survive independently in a forest, away from humans, is highly questionable. Some conservationists may even question if releasing humanised orangutans is simply a public relations move; one that could lead to the apes’ early death.

We continue to demand the SWD to show complete transparency on the management and futures of the six apes.

Orangutan humanisation

In orangutan conservation, humanisation refers to an orangutan’s over habituation to, and/or overdependence on, humans. It can fail an orangutan’s rehabilitation for forest release. Humanisation (and disease transmission) risks led the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) to conclude that tourism should not be allowed at orangutan rehabilitation centres.

Unscrupulous hands-on voluntourism practices at the SORC for over 15 years until early 2020, and contentious orangutan tourism may have well increased the risk of orangutan humanisation at the SORC, which could jeopardise the apes’ future. For 20 years until 2016, the SWD sanctioned the supply of orphan, infant SORC orangutans to a luxury hotel in Sabah for rehabilitation. We believe the primary purpose of this practice, which we campaigned against and stopped in 2016, was monetary gains, not rehabilitation.

According to conservationists, the effect of humanisation on orangutans undergoing rehabilitation can, among others:

- Encourage terrestriality, divert their interest away from natural behaviours and interactions within the forest environment

- Affect their nest building and foraging skills, thus hampering an orangutan’s chances of surviving in a forest

- Cause the apes to lose their fear of humans, making them far too comfortable with human presence and even seeking interaction with humans. This can increase their proximity to humans, which in turn can increase:

- the risk of attacks on both humans and orangutans

- the risk of contracting a disease from humans (e.g., hepatitis, tuberculosis, influenza)

- their vulnerability to poachers and hunters

Tweet to the SWD to demand transparency. CLICK HERE to tweet now. Sign and share our petition for the six apes

*The Tabin Wildlife Reserve is a 120,000 hectare protected forest reserve in East Sabah. It is surrounded by oil palm plantations

**When rehabilitant orangutans are released into a forest, researchers need to monitor them to ensure that they can adapt and survive, including to forage efficiently. During monitoring, vital data is collected. Monitoring also enables human intervention if an orangutan is unable to adjust or requires medical attention. Therefore, post-release monitoring (PRM) is also crucial for welfare reasons. The IUCN recommends PRM be conducted for at least one year. Only when an orangutan has consistently proven to adapt and survive independently can the ape’s rehabilitation be considered a success.

See our other posts about the Sepilok Orangutan Rehabilitation Centre:

Was an orangutan needlessly euthanised at Sepilok?

When profits rule – Sepilok orangutan release disaster

Sepilok orangutan tourism – here’s what’s wrong

What happened to the mothers of two orphaned Sepilok orangutans?

General public finally barred from involvement with orangutan rehab at Sepilok

Perilous orangutan tourism resumes at Sepilok amid COVID-19 pandemic

COVID-19: Time for change at Sepilok Orangutan Rehab Centre

SWD’s dubious plan to release two orphaned Sepilok orangutans